No Room For Error

Questions contributed by John Carney on December 8th, 2009.

Overview: Colonel Carney's interview focuses on his questions for building Air Force Special Tactics Units, leading The Special Operations Warrior Foundation, and performing with excellence.

* * * *

QuestionsForLiving: What questions did you ask yourself when you decided to become involved with Air Force Combat Control and special operations?

Carney: I was in a place called Ubon, Thailand in Southeast Asia, (it was classified at the time). We had just started building airbases there so that we could strike in northern Vietnam. That's when I first met some combat controllers. At that time, I didn't feel that I was contributing to the war effort as much as I wanted to -mainly because the job that I had was in personnel services. Once I met the combat controllers, I knew that the next time we were involved in any type of conflict like this I wanted to be in a position where I would be a "first-stringer" and really be contributing. I asked myself: "What is the best and most effective way I can contribute to this effort?" This comes back to my fundamental philosophy as a football coach: You need to contribute. If you're out there on the field, you've got to be someone who scores the touchdown, or contributing to scoring a touchdown, or stopping the opponent from getting one. You need to be contributing to the purpose of the team - I always had that in the back of my mind.

When my Air Force football career was coming to an end, I had a choice to get out of the Air Force and continue coaching or to stay the course in the Air Force. I decided that I would stay in the Air Force. That's when I fell back on my days in Southeast Asia and said "If I am going to be in the Air Force, I'm going to get involved in something that will really contribute."

That's when I chose to go to combat control. When I went into combat control I was not very well accepted. I was a passed over major, and the chances of me making major were slim to none. I said to myself: "I have made the decision to stay in the Air Force; now I've got to see if I can make the grade." So I approached everything from that day on with the attitude that I was going to give my utmost best every day, regardless of what the outcome was going to be in the future. The very present day was most important to me. I decided that every morning that I got up, I was going to do whatever they put in front of me to the best of my ability. I succeeded in doing that. I consistently asked: "Am I doing this task to the best of my ability?" I didn't worry about the future. I worried about my present job, present training, and the people around me. It was this focus on giving my very best, in the present moment, that carried me through some tumultuous years of not knowing what my future would be in the Air Force.

QFL: What were your primary questions for selecting the original team members for your first team known as Brand X?

Carney: I'm very strong on the aspect of a person's character. That was the most important criteria and the first thing that I wanted to know. I asked a lot of questions of people who had worked with these individuals for years. I looked at a guy that really wanted to succeed. I wanted a team player, a guy who would go the extra mile for his teammate, and had a history of being a team player. He had to be liked by other combat controllers. All the members of Brand X had to have a very good moral compass that was pointing in the right direction for me and the team.

Each member had to be a very experienced combat controller, and if they weren't, they had to have some other qualities that would make me swing in their favor. I gathered a team of about six that all had these strong qualities.

QFL: Am I correct in saying that from Brand X the Special Tactics teams were formed?

Carney: Absolutely. That was the precursor to Special Tactics today.

QFL: And then Special Tactics brought in other groups such as the PJs?

Carney: That's what happened. The combat controllers were terribly undermanned. The slots for PJs were earned by helicopter. There were two PJs earned for every helicopter and the Air Force decided not to purchase the full contingent of helicopters. So that left about 80 PJs vulnerable to being cut because the Air Force didn't buy all the helicopters they had planned to purchase.

Given that those manpower slots were not funded, I convinced General Mall and General Patterson to give me those positions. The idea was to bring them together with combat controllers and cross-train them. These guys had a lot of experience and I didn't want to see them go away. With the merger of the PJs, we could not call it "Combat Control Detachment" any longer so we changed it to "Special Tactics Detachment". This was a combination of Combat Controllers, PJs, and support people. So that's how that all started.

QFL: What were your core questions for building and training this group, once you had the initial team? In your book, you talked about trying to win the trust of Delta and SEAL Team Six. How did you train to achieve a level of performance that would instill confidence and trust with the other teams?

Carney: The way that I approached that was to get the team to buy into the fact that if we're going to add value to an operation, we need to be able to out army the Army and out SEAL the SEALs, if we have to. We simply had to be top notch professionals: "Why would Delta and SEAL Team Six not want to work with true professionals that are good at what they do... that are the best at what they do? I would constantly ask: How can we be the very best at the skills that we will be expected to know to accomplish our mission or task?

Regarding the actual training: First of all, we had to be in excellent physical shape. The rigors of the training back then were pretty tough on us, so we had to be in top physical condition. That was one requirement. However, the team also needed to know that there was a reason for them to be in good physical condition. Some of the conditions and standards we developed were challenging and you couldn't possibly perform them unless you are in top physical shape. I also wanted to make sure that they really understood all the tasks that we were expected to do to accomplish our mission. We would take the mission and look at all the ingredients that we would need to know about and train until we were experts in those skills. One my basic principles that was: "If we can't communicate, then we are worthless. If we can't get on that radio and contact the aircraft, or the army commander that were working to support, then we are worthless. We will always be able to communicate, and we will have redundant communications wherever we go." I was constantly asking myself: "How can we maintain and improve our ability to communicate?"

Several times we saved the day because we were able to communicate. Our ability to communicate made a big impact on the community.

QFL: Are there other core questions you were asking when you were training the team? You mentioned top physical condition, understanding all the tasks that people were expected to do, and the ability to communicate with each other.

Carney: Each team member really had to know their basic skills and had to be right at the top. There was no room for people to be shabby. They had to be at the top of their game. They had to look at all the things that we would be required to do - whether it was moving, communicating or shooting. We had to be able to do that, and we had to be the best at it. The Army, Navy, or whoever else we were supporting, felt that they could do it internally. My attitude was "No, you do not need to do that internally. We will do that for you." However first we had to go out and prove that we were the best at it. You cannot be the best unless you are physically fit and you know all the skills that you are expected to know and you hone those skills every day. Anyone who practices these skills every day should be good at them. Each team member knew that if they screwed up at one of those tasks, I would put them on the bench just like a football coach. Many a time I've sent a couple of them home from an exercise and said "Go home and regroup." We could not afford to mess up if an airplane with 60 paratroopers are relying on us. If you make a mistake, you are endangering a lot of lives. This team has quite a responsibility.

QFL: I remember in your book you said that over the course of your career, you were passed over for major a couple of times. However, although your career started slowly, it all of a sudden accelerated rapidly as you started to build these teams. Ultimately, you had an incredibly successful career in the Air Force. What were the primary questions that you asked yourself throughout your career?

Carney: I think the biggest questions that I would always ask myself were:

- Am I leaving something undone or is there something that I could be doing better?

- Is there some hole out there that I need to plug?

I needed to understand exactly what the special operations community was trying to accomplish and then what it was that I could do to be a force multiplier for the team. What can I do to enhance anything they're trying to do, whatever it is? So I had to be very knowledgeable of what was going on in the special operations arena.

- Where can I add value? I constantly asked that.

- Are we in the right area?

- Is that an area we should be in or is that an area that we should not be in, or bother with? I really focused. I didn't bother with anyone else's mission and I did not try to mission -creep into anyone else's area; I stayed focused on the path. Everyone must stay in their own lane. Once you start getting into everyone else's lane you start diluting what you're supposed to be doing. I asked "What is our niche?"

- What can we do to help bring this mission to a successful conclusion?

When I was passed over as a major before joining air combat control, there was no way that I could control all the different events. I could not control the promotion boards, the Air Force, or the direction they were going and the type of people that wanted. So all I could do was try to the best of my ability to prove to the special operations community that we were a force multiplier; we were a group that could contribute. It was not just me as an individual, but I had a team with me. As a team, we became indispensable to the mission.

QFL: What were your primary questions for leading the Special Operations Warrior Foundation?

Carney: I have been a member of the Special Operations Warrior Foundation since 1980. The foundation was started when we went over to rescue the hostages in Iran in 1980. We had the terrible accident and lost five airmen and three Marines. It was a terrible loss for special operations personnel, and these men left behind 17 children. At that time, we virtually vowed that we would see to their education. That became the mission. Unfortunately, throughout the 1980s, the foundation wasn't going anywhere. It wasn't out raising funds; it wasn't doing anything, but there were children coming in there that were eligible. I was asked by General Manor, the Chairman, and General Meyer, the Director, if I would become president.

At this time, I was a principal with Booz Allen and Hamilton as a defense consultant. I had my hands pretty well full. I was responsible for a $186 million dollar contract. I agreed to put together a plan for where the foundation should go in the future. I did that, and in that report I basically told them that there were a lot of stains on their robes. There was a period of three or four years when they did not raise a penny, and the money was sitting in the money markets in banks when it was the hottest stock market in our history. It was really poorly run, and I pointed that out to them. Well after I presented the information, they said "Well help us fix it." I said "No, I did my part. Here it is. I donated my funds and raised money." But I was the only one raising money. So I discussed it with my wife. It's just the two of us. We have children but they have grown up, and have their own life now. I said something inside me tells me that I would consider doing this. She said, "Do what your gut feels like doing." So I left a rather lucrative job and took this one over. And then again, I had to start all over building something. I started by asking myself "What is wrong with this organization?"

So I started learning more about the Foundation and nonprofit organizations. I peeled the onion back and looked at all the past minutes of each of the meetings. I looked at all the bylaws. I immersed myself in all the text I could find and devour on nonprofits. I studied it like I did with special tactics. I was asking "What is it that I can do to make this organization standout?" The first thing I came up with was we need to clearly articulate what our mission is to the public. I call this the elevator speech. From the time you step on the elevator and go up one floor, you ought to be able to tell someone your organization's mission and what you are doing with the public funds. So, the first thing that we did was to clearly define our mission. The second thing was that we needed to go out and put together a Board of Directors who is bought into this mission, and is willing to step up to the plate and help bring in the funds to enable us to do what we say we're going to do. Our mission is to educate the children of our fallen warriors. Previously, the Foundation would put someone through school only once we got enough money. To me that was an asinine way to do it. I said "We should just throw the gauntlet down and say "We are going to educate them.'" So that's the way we did it. I went out and started building a Board of Directors that were very much engaged and bought into the mission. Then I put together a program to go out to the public to share what we do at the Warrior Foundation and what our mission is. It basically grew from there. It is a noble cause. Why wouldn't anyone want to support it? I hired staff and I told the Board that "You have to have the organizational capacity to do this. You cannot sit around with volunteers that show up on one day or another. You've got to get a staff; you've got to pay a staff, and you have to get out there and do this like a business. So I hired an executive director, and a public relations director, and a couple of administrative people. We became a small nonprofit organization. Now I am simply sharing with the public our noble cause of supporting our men and women in special operations and their families.

In 1998, Special Operations Warrior Foundation had been operating for 18 years, and had only $700,000 in the bank. What a travesty. When I became president in 1998, I raised $1 million dollars, in the next year I raised $3 million, in the following year I raised $5 million. Today, we have $26 million in assets and more than 800 children in our program.

QFL: The last part of the interview has to do with the individual. What questions would you suggest that an individual ask him / herself to be able to achieve their own objectives without error?

Carney:

- Is your mission clearly stated?

- Do you have a clear vision of your mission and what you are trying to accomplish? You need to have a clear understanding of your mission.

- What is your job? You need to be able to clearly define your job. And then you need to know what are the key components to being successful in that job. You need to ask, "What is key in this job?"

- Are you very well read and articulate regarding all the fundamentals that go into being successful? Nobody's perfect but you should always be working to try to move towards that. I always ask myself that question.

QFL: What questions should individuals ask themselves to maintain their peak performance mentally and physically?

Carney:

- Am I as sharp in my job today as I was when I first took it over?

- Am I still asking every day "How can I take this to the top?"

- Am I treading water? Am I comfortable? Am I getting lackadaisical? Am I just taking things for granted? You have to avoid becoming complacent because if you're only treading water, sooner or later you're going to sink.

QFL: What are the questions for being able to operate in stressful situations?

Carney: I think you need to have a strong moral compass. There is such negativity that is being fed to us through the newspapers and the talk radio. It's just unbelievable some of the things that we are bombarded with. So you just need to have a strong faith, whatever that might be. You have to be very well attuned to understand that in your daily walk of life you're going to have some negative approaches to you. You are going to be faced with challenges. The only way to handle them is to first know that that's going to happen and that's life. You are not going to just walk down the street of life and have everything be just honky-dory. So you have to have a strong moral faith to understand that that's life and take it as calmly as you can, and understand what is right. Use your gut. "What is right and wrong here? Maybe this other person is right and I am wrong?" You have to be able to objectively understand what you're facing. You have to have strong moral faith and then have confidence in yourself that you understand right from wrong and know that you are always going to stick to your beliefs and do the right thing. There are times when I could be lazy and just take an easier road but that's not right and that would bother me so I don't do that. Once you set your principles, and what you believe in, and if you're always trying to do the right thing, it will carry you through. If you get into an emergency type of situation you will already be thinking that way and asking "What's the right thing to do here?"

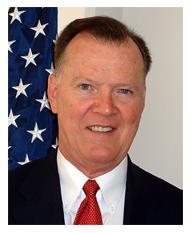

Colonel John Carney, Jr. can be contacted at:

or read Colonel Carney's book:

John Carney

Bio

Colonel John T. Carney Jr. has more than 30 years of professional experience, including 15 years commanding both Air Force and joint-service Special Operations units assigned to the Joint Special Operations Command, the Air Force Special Operations Command, and the United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM).

Colonel Carney's efforts in support of the Special Operations Community are well documented and spans more than two decades. He was at the forefront of operations planning and tactical execution of each and every mission involving our nation's Special Operations Forces (SOF) since the mid-1970's, including the Iranian hostage rescue mission in 1980, as well as special operations missions conducted in Grenada, Panama, Iraq, and Kuwait. During this period, he fielded professionally organized, trained, and equipped forces and developed comprehensive, combat-tested force employment procedures that continue to guide today's operations. His contributions were integral in paving the way for the successful rejuvenation of a solid national-level Special Operations capability.

In 1994, Colonel Carney was inducted into the Air Force Air Commando Hall of Fame and, in 1996, the Commander in Chief, USSOCOM presented Colonel Carney with the United States Special Operations Command Medal for outstanding contributions to Special Operations. He is a frequent lecturer at the Army Command and Staff College, Air War College and an adjunct instructor at the Air Force Special Operations School. In 2002 he co-authored "No Room for Error" telling the story of Special Tactics from Iran to Afghanistan.

In 2003, the National Defense Industrial Association's Special Operations and Low Intensity conflict Division awarded Colonel John Carney the 2003 R. Lynn Rylander Award for his outstanding service, dedication, and leadership to the special operations community.

In 2007, Colonel Carney's accomplishments earned him another prestigious honor “the Bull Simons Award" which recognizes special operators who embody the true spirit, values and skills of a special operations warrior, and named after the legendary Col. Arthur Bull Simons.

Colonel Carney has been involved with the Warrior Foundation since its inception in 1980 and is currently the President/CEO of the Special Operations Warrior Foundation, a top-rated nonprofit foundation that provides funding for college scholarships to the surviving children of Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps Special Operations Forces members who lost their lives in operational or training missions. The foundation also provides immediate financial assistance to severely wounded special operations personnel so their loved ones can be bedside during their recovery. Under Colonel Carney's leadership, in less than ten years, the Foundation's assets have grown from $800,000 to $29 million, thus ensuring the four-year college educations for more than 800 surviving children of fallen special operations warriors.

Homepage

http://www.specialops.org/